No student enters the classroom as a blank slate. Each has prior knowledge, also known as background knowledge, which informs their approaches to and understanding of new material and new experiences. Prior knowledge is the accumulation of everything a student has learned, through both formal and informal means. We can help students better understand new material by activating their prior knowledge, or, to put it another way, we can help them access their existing schema to better facilitate the learning of new knowledge and skills.

What is a Schema?

What exactly is a schema? Schemata, as it is known in the plural form, are the cognitive structures composed of facts and concepts that are arranged into meaningful organizations of relationships. Our brains are constantly arranging new information, such as events, places, people, and ideas, into systems that help us interpret the world. Cross (1999) described schemata this way:

A schema is a cognitive structure that consists of facts, ideas, and associations organized into a meaningful system of relationships. People have schemata for events, places, procedures, and people, for instance. Thus, a schema is an organized collection of bits of information that together build the concept of the college for each individual. When someone mentions the college, we “know” what that means, but the image brought to mind may be somewhat different for each individual. (p. 8)

As we receive new information and undergo new experiences, our schemata adapt and grow, reorganizing and connecting new ideas to the existing structure to establish meaning and understanding.

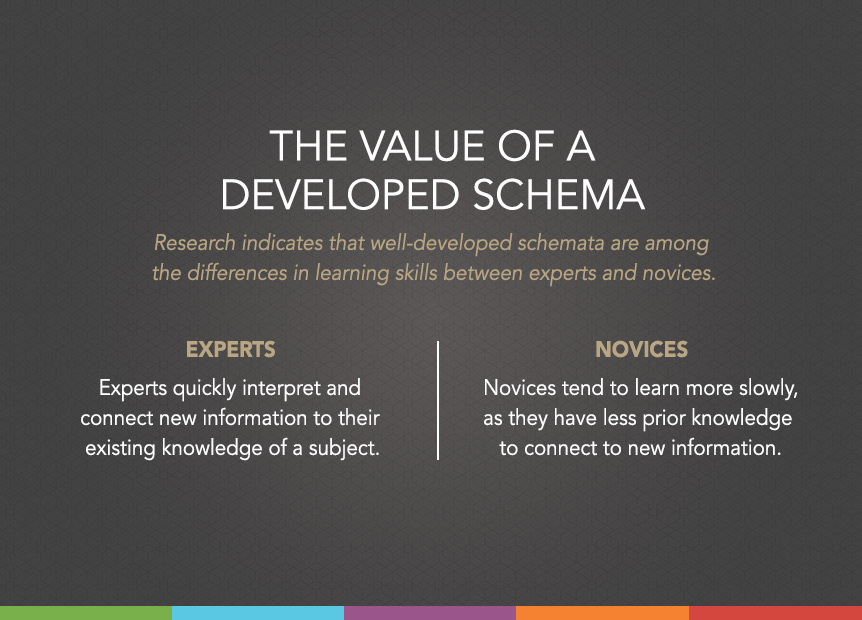

The Value of a Developed Schema

While everyone has a vast collection of schemata, each schema is not necessarily well-developed. Research indicates that well-developed schemata are among the differences in learning skills between experts and novices. Experts demonstrate the value of a well-developed schema by quickly interpreting and connecting new information to their existing knowledge. They have numerous connections to draw from compared to a novice of the subject. Novices learn more slowly and with greater effort, not because they are necessarily less intelligent, but because they have less prior knowledge to connect to the new information. With a less developed schema, they aren’t as able to organize the new information (Cross, 1999, p. 8; de Groot, 1966).

Each schema evolves and develops over the course of an individual’s life, filtering new events by perception and reorganizing them into the existing knowledge structure in order to establish meaning. However, new material can only generate meaningful learning if it can be connected to knowledge that already exists in the student’s mind, altering their schema and establishing the connections necessary for understanding.

What Activating Prior Knowledge Means

We can help students learn new material by activating their prior knowledge (i.e., helping them access their schemata) in order to establish connections with lessons and new material. If we understand what students already know, we’ll know how to build on that and identify what remains to be learned.

Challenges to Activating Prior Knowledge

Activating prior knowledge does pose challenges. Two of the key hurdles are insufficient prior knowledge and students’ misconceptions.

Insufficient Prior Knowledge

Students may enter the classroom with gaps in their existing knowledge. Clearly, students are better able to learn if they have sufficient and accurate existing knowledge (Ambrose et al., 2010). Students may struggle to learn, particularly, if their knowledge gaps are relevant to the new material or tasks (Chew & Cerbin, 2021). Without the necessary foundational knowledge, students may not be able to activate their schemata to develop new knowledge. However, students may not always be able to identify their own knowledge gaps (Dunning, 2007), so it is essential for us to determine where their knowledge is insufficient.

Misconceptions

Some students have prior knowledge that isn’t simply insufficient, it is inaccurate. Students have misconceptions when they enter the classroom with knowledge that is incorrect. Certainly, learning suffers when it is built on a flawed foundation of knowledge. Students may be prone to misunderstand new material or even ignore new ideas altogether if they don’t connect with their existing schemata. Misconceptions can be a more challenging hurdle than insufficient knowledge because students are often resistant to correction and reorientation (Taylor & Kowalski, 2014). Additionally, there are times when students will momentarily cast aside their misconceptions but revert to them once a lesson or course has ended (Chew & Cerbin, 2021).

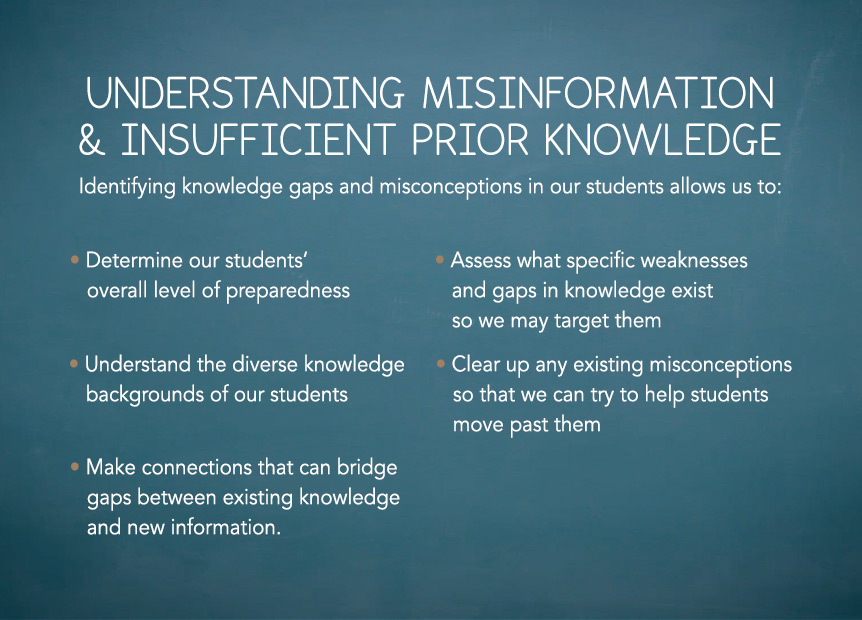

Student learning is hindered by misinformation as well as insufficient prior knowledge. Understanding these knowledge gaps in our students will help us steer students toward stronger outcomes by equipping us to:

- Determine our students’ overall level of preparedness

- Assess what specific weaknesses and gaps in knowledge exist so we may target them

- Clear up any existing misconceptions so that we can try to help students move past them

- Understand the diverse knowledge backgrounds of the students in our classes

- Make connections that can bridge the gaps between existing knowledge and new information.

Techniques for Activating Prior Knowledge

We can improve our students’ capacity for learning by guiding their initial preparation and beginning class sessions or modules by helping them access their schemata. It’s common for teachers to consider their lectures and presentations as the beginning of a new learning unit, but studies indicate that if we engage students’ prior information before introducing new information, we can improve their knowledge retention from the lecture. Lectures become more effective if students have the preparation to connect their background knowledge to the subject. This can also help mitigate the impact of students beginning the course with differing knowledge of the subject.

Two methods for activating prior knowledge are to assign pre-instructional activities and to stimulate student interest in the subject. The following Cross Academy Techniques can help students invoke schemata and in turn better retain recent information:

Advance Organizers:

You can help students structure the information they will learn during a lecture by providing them with a visual tool for organizing information at the start of a course or class period.

View main video here: View Technique →

View online adaptation here:

Update Your Classmate:

At the beginning of a class period, ask students to engage in a brief writing activity where they explain the material from a previous period to a real or fictional student who missed the class.

View main video here: View Technique →

View online adaptation here:

Sentence Stem Predictions:

With Sentence Stem Predictions (SSPs), students are given an incomplete sentence designed to encourage students to predict what may be discussed in the forthcoming lecture.

View main video here: View Technique →

View online adaptation here:

Email us to receive information about new blog posts.

References:

Ambrose, S. A., Bridges, M. W., DiPietro, M., Lovett, M., Norman, M., & Mayer, R. (2010). How learning works: Seven research-based principles for smart teaching. Jossey-Bass.

Chew, S. L., Cerbin. W. J. (2021). The cognitive challenges of effective teaching. The Journal of Economic Education, 52(1), 17-40.

Cross, K.P. (1999). Learning is about making connections: The Cross Papers #3. League for Innovation in the Community College.

de Groot, A. (1966). Perception and memory versus thought: Some old ideas and recent findings. In B. Kleinmuntz (Ed.), Problem solving: research, methods, and theory. Wiley.

Dunning, D. (2007). Self-insight: Roadblocks and detours on the path to knowing thyself. Taylor

& Francis.

Taylor, A. K., & Kowalski, P. (2014). Student misconceptions: Where do they come from and what can we do? In V. A. Benassi, C. E. Overson, & C. M. Hakala (Eds.), Applying science of learning in education: Infusing psychological science into the curriculum (pp. 259-273). Society for the Teaching of Psychology. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1085109.pdf

Suggested Citation

Barkley, E. F., & Major, C. H. (n.d.). Exploring schema in your class: Techniques to activate prior knowledge. CrossCurrents. https://kpcrossacademy.ua.edu/schema-activating-prior-knowledge/

Engaged Teaching

A Handbook for College Faculty

Available now, Engaged Teaching: A Handbook for College Faculty provides college faculty with a dynamic model of what it means to be an engaged teacher and offers practical strategies and techniques for putting the model into practice.