Few of us have had formal opportunities to learn about teaching online. As a result, we often lack a full understanding, or even a good practical sense, of the look, pacing, and feel of an online course. But to teach online well, we need such knowledge.

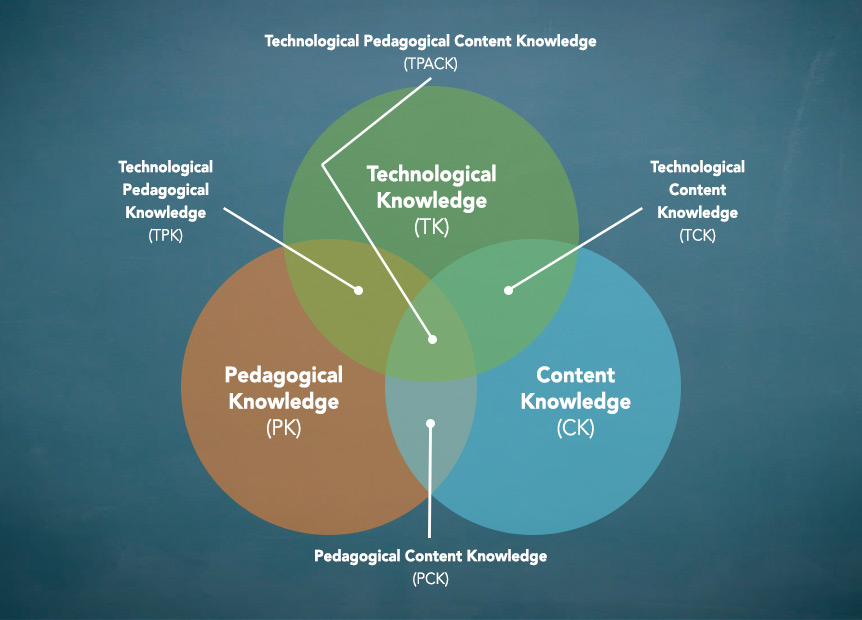

Lee Shulman, educational psychologist and former president of the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, suggested that faculty possess content knowledge (CK), which includes the theories, principles, and concepts of a particular discipline. This kind of knowledge is what many of us develop in graduate school. We also typically have a general pedagogical knowledge (PK), or knowledge about teaching itself. Of these two areas of knowledge, Shulman asks the following question: “Why this sharp distinction between content and pedagogical process?”

Pedagogical Content Knowledge (PCK)

A way of knowing that is unique to teachers who take an aspect of subject matter, organize and present the material, and through pedagogical choices, transform it into something that learners can comprehend.

For Shulman, having knowledge of two distinct areas – knowledge of the content of the faculty member’s discipline and knowledge of general pedagogical techniques – is insufficient. He argues that there is an overlap between those areas in which effective teaching happens. His conception of pedagogical content knowledge (PCK), then, is the blend of subject matter knowledge and general pedagogical knowledge.

He describes pedagogical content knowledge as “that special amalgam of content and pedagogy that is uniquely the province of teachers, their own special form of professional understanding.” Pedagogical content knowledge, then, is a way of knowing that is unique to teachers who take an aspect of subject matter, organize and present the material, and through pedagogical choices, transform it into something that learners can comprehend.

Technical Pedagogical

Content Knowledge (TPACK)

Knowledge that represents the intersections of pedagogy and content, of technology and content, and of technology and pedagogy.

But when we teach online, we have a need for a different kind of knowledge. Extending Shulman’s ideas about pedagogical content knowledge, Mishra and Koehler suggest that when teaching online, teachers need not only content knowledge and pedagogical knowledge, but also technological knowledge. They further argue that the interaction among these three bodies is important and illustrate their concept of Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPACK) in the following figure:

TPACK advances the notion that faculty who teach online need new and different knowledge and expertise than those who teach onsite. Such knowledge transcends the three individual knowledge areas and represents a different form of integrated and synthesized knowledge.

Thus, instructors who teach online need content knowledge, pedagogical knowledge, and technological knowledge. They also need knowledge that represents the intersections of pedagogy and content, of technology and content, and of technology and pedagogy. If any areas are not as well developed as they should be, then interactions amongst them are not as powerful as they could be. Indeed, if the interactions fail to occur, then teaching and learning suffer. This latter point is essential. Knowledge of any of the three main areas alone is insufficient for effective online teaching. It is the area of overlaps that are critical. Instead of simply adding new knowledge of technology to content knowledge and pedagogical knowledge, faculty instead should develop knowledge about the ways in which technology and content interact as well as the ways in which technology and pedagogy interact.

Sources for Learning About Teaching Online

Sources for Learning About Teaching Online

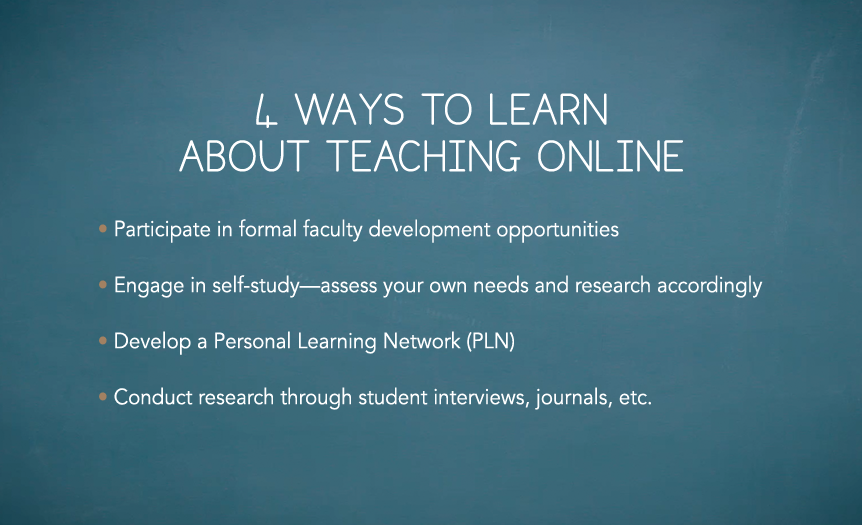

When trying to learn about teaching online, there are several key ways to go about it, and we offer the following suggestions:

Participate in any Available Formal Opportunities

Faculty development opportunities often are available at our institutions, and during the COVID-19 pandemic, many institutions have ramped up opportunities for faculty to learn to teach online. Some institutions offer lectures and workshops aimed at helping faculty members learn specific technologies, such as learning management systems. Fewer institutions offer sessions about pedagogy and technology. Participating in both learning opportunities can provide us with the theoretical expertise that can form the basis of our technological pedagogical content knowledge.

Engage in Self-study

Consider a do-it-yourself (DIY) approach to learning how to teach online. A DIY approach puts us in charge of what to learn, allowing us to assess what we know and what we do not know and then to make key decisions about how to fill in the gaps. During the pandemic, many institutions have curated a range of sources on learning how to teach online. Many of them include some of the videos and other resources we have shared here at the K. Patricia Cross Academy.

Develop a Personal Learning Network

A Personal Learning Network (PLN) is a group of people who can help guide learning, identify learning opportunities, answer questions, and be a center of knowledge and experience. Developing a PLN can provide you with a source of support when teaching online. They can include assistance across a wide spectrum of expertise, thus being potentially helpful to someone whether they are an early adopter or a novice. PLNs lend themselves particularly well to those who are teaching online, since they often are developed through social media such as Twitter, LinkedIn, or Facebook.

Conduct Research

Faculty who are interested in developing knowledge to improve their online teaching effectiveness can gather data from students about what students know or need to know. Data collected from students can include the following:

- interviews

- focus groups

- activity or time logs

- self-reflections

- virtual field notes

- journals

- formative assessments, such as:

Background Knowledge Probe

A Background Knowledge Probe is a short, simple, focused questionnaire that students fill out at the beginning of a course or start of a new unit that helps teachers identify the best starting point for the class as a whole.

View main video here: View Technique →

View online adaptation here:

Individual Readiness Assurance Tests (IRATS)

Individual Readiness Assurance Tests are closed-book quizzes that students complete after an out-of-class reading, video, or other homework assignment.

View main video here: View Technique →

View online adaptation here:

Quick Write

A Quick Write is a learning assessment technique where learners respond to an open-ended prompt.

View main video here: View Technique →

View online adaptation here:

Teaching online requires and instills new ways of knowing, new types of knowledge, and new ways of developing knowledge. These new forms of knowledge add to what teachers typically must know and do in order to fulfill their roles as teachers. In particular, teaching online requires that we learn about technology and the way that it intersects with both content and pedagogy. Doing so requires additional effort, but it can also help us to understand both content and pedagogy in new ways. Adding in technological knowledge, then, has the potential to develop our knowledge bases and ultimately has the potential to help us improve as teachers.

To sign up for our newsletter, where you will receive information about future blog posts, email us.

Reference:

Major, C. H. (2015). Teaching online and instructional change: A guide to theory, research, and practice. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Suggested Citation

Barkley, E. F., & Major, C. H. (n.d.). From PCK to TPACK: Essential knowledge for teaching online. CrossCurrents. https://kpcrossacademy.ua.edu/from-pck-to-tpack-knowledge-for-teaching-online/

Engaged Teaching

A Handbook for College Faculty

Available now, Engaged Teaching: A Handbook for College Faculty provides college faculty with a dynamic model of what it means to be an engaged teacher and offers practical strategies and techniques for putting the model into practice.